Aflevering 20 - "Vae Victis"

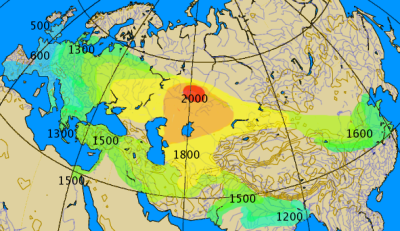

De oorsprong van de indo-Europese volkeren, waar de Kelten haar oorsprong in vinden.

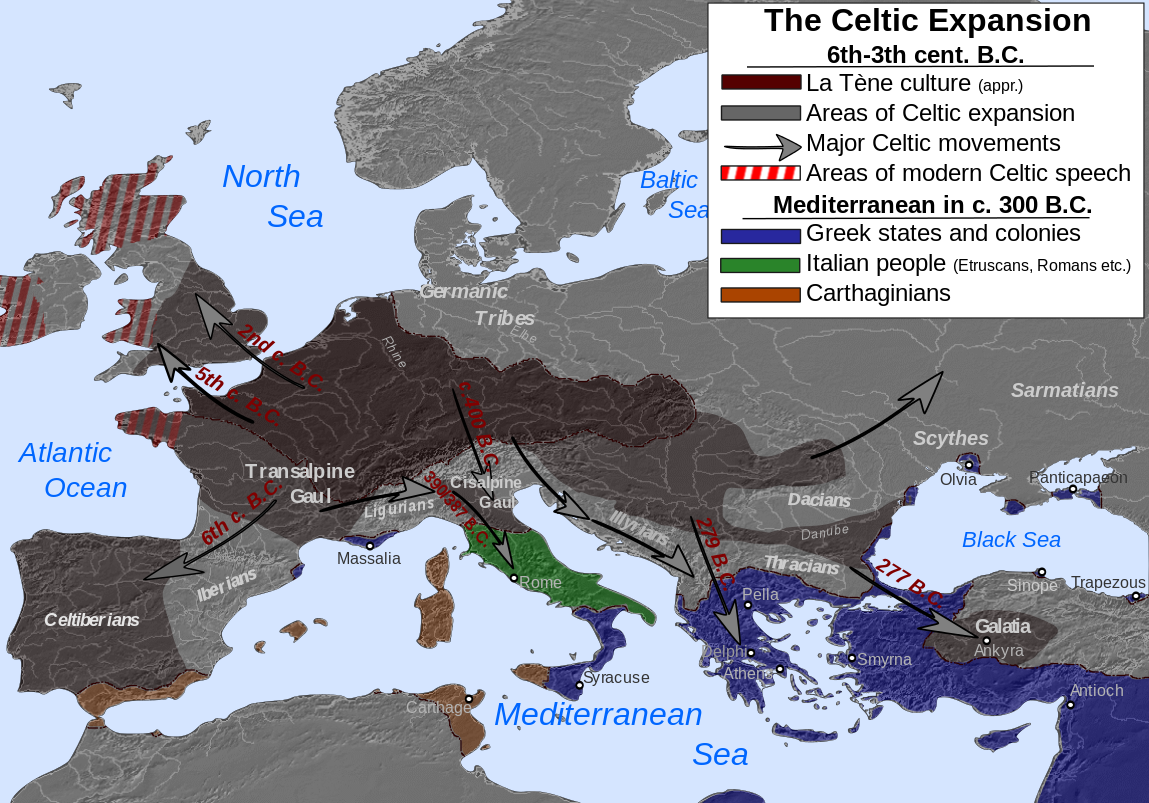

Een kaart van de verspreiding van de Keltische cultuur van 600 - 300 v. Chr.

Overzicht van de Hallstatt (geel) en de latere La Tène cultuur (groen) en de verspreiding door Europa.

Op deze kaart is ook het leefgebied van de verschillende Keltische stammen in kaart gebracht. De Senones leefden oorspronkelijk in midden tot Oost-Frankrijk. Op deze kaart zie je echter ook de Senones weergegeven aan de Oost-kust van Italië. Dit is de locatie waar ze neerstreken na de migratie.

Lees hier over Adriatische Veneti.

(Zie het stukje over History - Pre Roman Period, hier staat de verklaringen van Strabo opgenomen over de paardenhandel tussen Syracuse en de Veneti)

Op deze kaart is o.a. de Griekse stadstaat Massalia (hedendaags Marseille) te zien in Zuid-Frankrijk.

Door te handelen met deze stadstaat leerden de Galliërs wijn kennen, en dit is ook de staat die de Galliërs een weg over de alpen wees.

Een goede weergave van de Slag bij de Allia.

Dit fragment is afkomstig van het kanaal 'Kings & Generals'. Bezoek ze hier.

Een buste van Brennus.

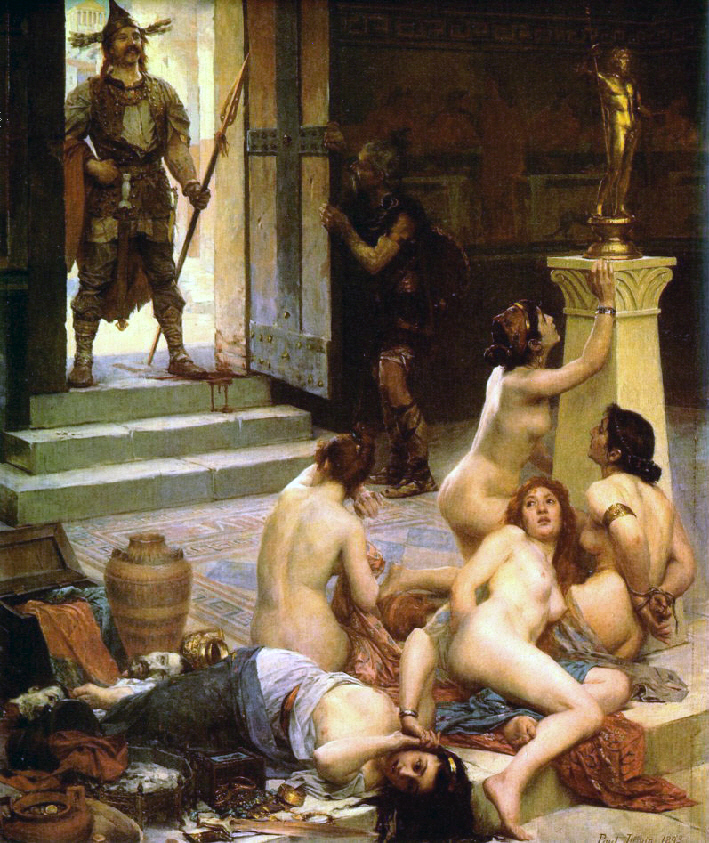

Brennus en 'zijn deel van de buit'.

'Brennus and His Share of the Spoils' - Paul Jamin (1893)

Brennus tijdens zijn beroemde "Vae Victis".

Lees hier over de Peloponnesische oorlog en de Siciliaanse expeditie.

De rede van Marcus Furius Camillus die voorkwam dat de Romeinen Rome zouden verruilen voor Veii.

(klik hier voor alle boeken van Livius)

“Romans, so strong is my aversion from holding contentions with the tribunes of the people, that while I resided at Ardea, I had no other consolation in my melancholy exile than that I was at a distance from such contests; and, on account of these, I was fully determined never to return, even though ye should recall me by a decree of senate and order of the people. Nor was it any change of my sentiments, which induced me now to revisit Rome, but the situation of your affairs. For the point in question was, not whether I should reside in my native land, but whether that land, (if I may so express myself,) should keep in its own established seat? And on the present occasion most willingly would I remain silent, did not this struggle also affect the essential interests of my country; to be wanting to which, as long as life remains, were base in others, in Camillus infamous. For to what purpose have we laboured its recovery? Why have we rescued it out of the hands of the enemy? After it has been recovered, shall we voluntarily desert it? Notwithstanding that the capitol and citadel continued to be held and inhabited by the gods and the natives of Rome, even when the Gauls were victorious, and in possession of the whole city; notwithstanding that the Romans are now the victors; shall that capitol and citadel be abandoned with all the rest, and our prosperity become the cause of greater desolation, than our adversity was? In truth, if we had no religious institutions which were founded together with the city, and regularly handed down from one generation to another; yet the divine power has been so manifestly displayed at this time in favour of the Roman affairs, that I should think all disposition to be negligent in paying due honour to the gods effectually removed from the minds of men. For, take a review of the transactions of these latter years in order — prosperous and adverse — ye will find that in every instance prosperity constantly attended submission to the immortals, and adversity the neglect of them. To begin with the war of Veii: for what a number of years, and with what an immensity of labour, was it carried on? Yet it could not be brought to a conclusion, until, in obedience to the admonition of the gods, the water was discharged from the Alban lake. Consider, did this unparalleled train of misfortunes, which ruined our city, commence until the voice sent from heaven, concerning the approach of the Gauls, had been disregarded; until the laws of nations had been violated by our ambassadors; and until we, with the same indifference towards the deities, passed over that crime which we were bound to punish? Vanquished, therefore, made captives, and ransomed, we have suffered such punishments at the hands of gods and men, as render us a warning to the whole world. After this, our misfortunes again reminded us of our duty to the heavens. We fled for refuge into the capitol, to the mansion of Jupiter, supremely good and great. The sacred utensils, amidst the ruin of our own properties, we partly concealed in the earth, partly conveyed out of the enemy’s sight, to the neighbouring cities. Abandoned by gods and men, yet we did not intermit the sacred worship. The consequence was, they restored us to our country, to victory, and to our former renown in war, which we had forfeited; and on the heads of the enemy, who, blinded by avarice, broke the faith of a treaty in respect to the weight of the gold, they turned dismay, and flight, and slaughter.

LII. “When ye reflect on these strong instances of the powerful effects produced on the affairs of men by their either honouring or neglecting the deity, do ye not perceive, Romans, what an act of impiety we are about to perpetrate, even in the very moment of emerging from the wreck and ruin which followed our former misconduct? We are in possession of a city built under the direction of auspices and auguries, in which there is not a spot but is full of gods and religious rites. The days of the anniversary sacrifices are not more precisely stated, than are the places where they are to be performed. All these gods, both public and private, do ye intend, Romans, to forsake? What similitude does your conduct bear to that, which lately, during the siege, was beheld, with no less admiration by the enemy than by yourselves, in that excellent youth Caius Fabius, when he went down from the citadel through the midst of Gallic weapons, and performed on the Quirinal hill the anniversary rites pertaining to the Fabian family? Is it your opinion that the religious performances of particular families should not be intermitted, though war obstruct, but that the public rites and the Roman gods should be forsaken even in time of peace; and that the pontiffs and flamens should be more negligent of those rites of religion than was a private person? Some, perhaps, may say, we will perform these at Veii; we will send our priests thither for that purpose: but this cannot be done without an infringement of the established forms. Even in the case of the feast of Jupiter, (not to enumerate all the several gods, and all the different kinds of sacred rites,) can the ceremonies of the lectisternium be performed in any other place than the capitol? What shall I say of the eternal fire of Vesta; and of the statue, that pledge of empire, which is kept under the safeguard of her temple? What, O Mars Gradivus, and thou, Father Quirinus, of thy Ancilia?* Is it right that those sacred things, coeval with the city, nay some of them more ancient than the city itself, should all be abandoned to profanation? Now, observe the difference between us and our ancestors. They handed down to us certain sacred rites to be performed on the Alban, and on the Lavinian mounts. Was it then deemed not offensive to the gods, that such rites should be brought to Rome, and from the cities of our enemies; and shall we, without impiety, remove them from hence to an enemy’s city, to Veii? Recollect, I beseech you, how often sacred rites are performed anew, because some particular ceremony of our country has been omitted through negligence or accident. In a late instance, what other matter, after the prodigy of the Alban lake, proved a remedy for the distresses brought on the commonwealth by the war of Veii, but the repetition of them, and the renewal of the auspices? But besides, as if zealously attached to religious institutions, we have brought not only foreign deities to Rome, but have established new ones. It was but the other day that imperial Juno was removed hither from Veii; and with what a crowded attendance was her dedication on the Aventine celebrated? And how greatly was it distinguished by the extraordinary zeal of the matrons? We have passed an order for the erecting of a temple to Aius Locutius in the new street, out of regard to the heavenly voice which was heard there. To our other solemnities we have added Capitoline games, and have, by direction of the senate, founded a new college for the performance thereof. Where was there occasion for any of these institutions, if we were to abandon the city at the same time with the Gauls; if it was against our will that we resided in the capitol for the many months that the seige continued; if it was through a motive of fear that we suffered ourselves to be confined there by the enemy? Hitherto we have spoken of the sacred rites and the temples, what are we now to say of the priests? Does it not occur to you, what a degree of profaneness would be committed with respect to them? For the vestals have but that one residence, from which nothing ever disturbed them, except the capture of the city. It is deemed impious if the Flamen Dialis remain one night out of the city. Do ye intend to make them Veientian priests instead of Roman? And, O Vesta, shall thy virgins forsake thee? And shall the flamen, by foreign residence, draw every night on himself and the commonwealth so great a load of guilt? What shall we say of other kinds of business which we necessarily transact under auspices, and almost all within the Pomœrium? To what oblivion, or to what neglect, are we to consign them? The assemblies of the curias, which have the regulation of military affairs; the assemblies of the centuries, in which ye elect consuls and military tribunes; where can they be held under auspices, except in the accustomed place? Shall we transfer these to Veii? Or shall the people, in order to hold their meetings, lawfully crowd together here, with so great inconvenience, and into a city deserted by gods and men?

LIII. “But it is urged that the case itself compels us to leave a city desolated by fire and ruin, and remove to Veii, where every thing is entire, and not to distress the needy commons by building here. Now, I think, Romans, it must be evident to most of you, though I should not say a word on the subject, that this is but a pretext held out to serve a purpose, and not the real motive. For ye remember, that this scheme of our removing to Veii was agitated before the coming of the Gauls, when the buildings, both public and private, were unhurt, and when the city stood in safety. Observe, then, tribunes, the difference between my way of thinking and yours. Ye are of opinion, that even though it were not advisable to remove at that time, yet it is plainly expedient now. On the contrary, and be not surprised at what I say until ye hear my reasons, even allowing that it had been advisable so to do, when the whole city was in a state of safety, I would not vote for leaving these ruins now. At that time, removing into a captured city from a victory obtained, had been a cause glorious to us and our posterity; but now, it would be wretched and dishonourable to us, while it would be glorious to the Gauls. For we shall appear not to have left our country in consequence of our successes, but from being vanquished; and by the flight at the Allia, the capture of the city, and the blockade of the capitol, to have been obliged to forsake our dwellings, and fly from a place which we had not strength to defend. And have the Gauls been able to demolish Rome, and shall the Romans be deemed unable to restore it? What remains, then, but that ye allow them to come with new forces, for it is certain they have numbers scarcely credible, and make it their choice to dwell in this city, once captured by them, and now forsaken by you? What would you think, if, not the Gauls, but your old enemies the Æquans or Volscians, should form the design of removing to Rome? Would ye be willing that they should become Romans, and you Veientians? Or would ye that this should be either a desert in your possession, or a city in that of the enemy? Any thing more impious I really cannot conceive. Is it out of aversion from the trouble of rebuilding, that ye are ready to incur such guilt and such disgrace? Supposing that there could not be erected a better or more ample structure than that cottage of our founder, were it not more desirable to dwell in cottages, after the manner of shepherds and rustics, in the midst of your sacred places and tutelar deities, than to have the commonwealth go into exile? Our forefathers, a body of uncivilized strangers, when there was nothing in these places but woods and marshes, erected a city in a very short time. Do we, though we have the capitol and citadel safe, and the temples of the gods standing, think it too great a labour to rebuild one that has been burned? What each particular man would have done, if his house had been destroyed by fire, should the whole of us refuse, in the case of a general conflagration?

LIV. “Let me ask you, if, through some ill design or accident, a fire should break out at Veii, and the flames being spread by the wind, as might be the case, should consume a great part of the city: must we seek Fidenæ, or Gabii, or some other city, to remove to? Has our native soil so slight a hold of our affections; and this earth, which we call our mother? Or does our love for our country extend no farther than the surface, and the timber of the houses? I assure you, for I will confess it readily, that during the time of my absence, (which I am less willing to recollect, as the effect of ill treatment from you, than of my own hard fortune,) as often as my country came into my mind, every one of these circumstances occurred to me; the hills, the plains, the Tiber, the face of the country to which my eyes had been accustomed, and this sky, under which I had been born and educated; and it is my wish, Romans, that these may now engage you, by the ties of affection, to remain in your own established settlements, rather than hereafter prove the cause of your pining away in anxious regret at having left them. Not without good reason did gods and men select this spot for the building of Rome, where are most healthful hills, a commodious river, whose stream brings down the produce of the interior countries, while it opens a passage for foreign commerce; the sea, so near as to answer every purpose of convenience, yet at such a distance as not to expose it to danger from the fleets of foreigners: and in the centre of the regions of Italy, a situation singularly adapted by its nature to promote the increase of a city. Of this the very size, as it was, must be held a demonstration. Romans, this present year is the three hundred and sixty-fifth of the city; during so long a time have ye been engaged in war, in the midst of nations of the oldest standing: yet, not to mention single nations, neither the Æquans in conjunction with the Volscians, who possess so many and so strong towns, nor the whole body of Etruria, possessed of such extensive power by land and sea, and occupying the whole breadth of Italy, from one sea to the other, have shown themselves equal to you in war. This being the case, where can be the wisdom in making trial of a change, when, though your valour might accompany you in your removal to another place, the fortune of this spot could not certainly be transferred? Here is the capitol, where a human head being formerly found, it was foretold that in that spot should be the head of the world, and the seat of sovereign empire. Here, when the capitol was to be cleared by the rites of augury, Juventas and Terminus, to the very great joy of our fathers, suffered not themselves to be moved. Here is the fire of Vesta, here the Ancilia sent down from heaven, here all the gods, and they, too, propitious to your stay.” Camillus is said to have affected them much by other parts of his discourse, but particularly by that which related to religious matters. But still the affair remained in suspense, until an accidental expression, seasonably uttered, determined it. For in a short time after this, the senate sitting on this business in the Curia Hostilia, it happened that some cohorts, returning from relieving the guards, passed through the Forum in their march, when a centurion in the Comitium called out, “Standard-bearer, fix your standard. It is best for us to stay here.” On hearing which expression, the senate, coming forth from the Curia, called out with one voice, that “they embraced the omen;” and the surrounding crowd of commons joined their approbation. The proposed law being then rejected, they set about rebuilding the city in all parts at once. Tiles were supplied at the public expense, and liberty granted to hew stones and fell timber, wherever each person chose, security being taken for their completing the edifices within the year. Their haste took away all attention to the regulation of the course of the streets: for setting aside all regard to distinction of property, they built on any spot which they found vacant. And that is the reason that the old sewers, which at first were conducted under the public streets, do now, in many places, pass under private houses, and that the form of the city appears as if force alone had directed the distribution of the lots.

Reacties

Een reactie posten